Lifestyle and Longevity: Stating the Obvious

Ultimately, the best use of an individual’s resources is perpetuating that individual’s existence. And whilst that might seem a little too selfish for some, it’s pretty close to the biological reality for most species. Humans however have a unique ability to influence our longevity through the choices we make for our own biological systems. This is true for humankind collectively – and it is entirely possible, if not likely, that the choices we make during this millennium will lead to the extinction of our species. It is also true on an individual basis. We can materially influence our longevity by the choices we make for ourselves. There is minimal room for fatalist philosophy when it comes to our individual biologies, genetic predispositions aside. Whilst there is still much of the inner workings of our bodies that we do not understand, we know enough to understand that the answers will be scientific.

And yet, medical science, for all of its genius invention and discovery, has strangely subordinated the science of prevention to the science of cure. It is systematic. The UK’s national health budget is divided up 97/8 in favour of treatment and cure versus prevention. A medical student in the UK will spend 5 or more years learning about the body, what goes wrong and how to fix it but only a few mornings worth of lectures on how human lifestyles and environmental factors cause us to become ill in the first place. It’s not meaningfully different in the US or, say, Germany with average tuition time on nutrition somewhere between 10 and 20 hours in total across the entire medical degree. Indeed, studies show that plenty of doctors in these ‘advanced’ countries don’t believe nutrition to be relevant to their work.

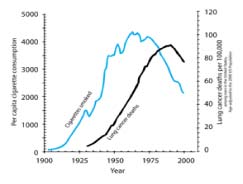

No surprise perhaps, with hindsight, that we spent the best part of a century concluding that smoking causes lung cancer despite the evidence in front of us from around the 1940s if not earlier.

Correlation Between Smoking and Lung Cancer in the USA

And we are still paying the price, in lives and dollars, for that wilful blindness. The American Cancer Society estimates that as recently as 2017, there were 222,500 new lung cancer cases diagnosed in the United States and 155,870 lung cancer deaths. Consider all of the resources we have spent finding cures and funding treatments and all we had to do, more or less, at a statistically irrefutable level, was persuade or legislate for people to give up smoking. The cost on lives is bad enough but for health services and insurers facing exploding costs for ageing populations, the monetary costs are ruinous. According to the National Institute of Health in the US, in 2017 the chemotherapy and radiation treatment costs for lung cancer patients enrolled in the federal Medicare system ranged from $4242 to $8287 per month during the initial six months of care and the cost for surgery was $30,096.

Thankfully, lung cancer cases are on the decline in those countries that have acted to educate their citizens of the risk that smoking brings. The bigger question now is whether we have really learned the lesson from smoking and lung cancer – that our lifestyles really do have a material impact on our longevity. Depressing data points on other diseases suggests that we have not. Many cancers, cardiovascular disease, stroke, dementia, and diabetes all have unhealthy lifestyles as a material risk factor, and some are rising as rapidly as lung cancer did in the 20th Century.

For example, since 1996, the number of people diagnosed with diabetes in the UK has risen from 1.4 million to 3.5 million. With another 500,000 estimated to have the disease that remain undiagnosed, this amounts to around 1 in 16 of the population of the United Kingdom currently living with diabetes. Diabetes is a killer resulting in an overall reduction in life expectancy of more than 20 years for Type I and 10 years for Type II. It is also estimated that as much as 10% of the NHS annual budget is now utilised in the treatment of diabetes, equal to around £173 million per week. That’s more than the £8 billion the UK government spends annually on the police service. Type II diabetes makes up around 90% of all cases and there is irrefutable evidence that lifestyle factors summed up in the term ‘obesity’ are a material risk factor for developing Type II diabetes.

Moreover, epidemiologic evidence suggest that people with diabetes are at significantly higher risk of developing many forms of cancer and it is established that Type II diabetes and cancer share many risk factors. A recent study published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute goes further in finding that new-onset diabetes may be an early indication of pancreatic cancer, the world’s toughest cancer, with survival rates often measured in months. Another clear indication that much cancer is lifestyle and environmentally driven is the rapid increase in incidence seen in the developing world where lifestyles, especially diet, have changed so rapidly over the last few decades. The WHO projects that the global cancer incidence will increase from 14 million in 2012 to 22 million in 2032, with more than 60% of incident cancers and 70% of cancer deaths occurring in central and south America, Africa, and Asia.

Other less well-known diseases are catching up and we have yet to allocate them to the ‘lifestyle disease’ category despite growing evidence. For example, the US Center for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) estimated that between 1999 and 2015 the incidence of Inflammatory Bowel Syndrome (either Chrohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis) had increased from 2 million to 3 million US adults. The CDC also reports that the prevalence of food allergy in children increased by 50 percent between 1997 and 2011. Each year in the US, c.200,000 people require emergency medical care for allergic reactions to food and childhood hospitalizations for food allergy tripled between the late 1990s and the mid-2000s. Although researchers have yet to determine the precise reason for these major increases, evidence is emerging that our lifestyles and environmental factors including what we eat, where we live and the air we breathe are material risk factors.

Medical researchers currently investigating the human gut microbiome are perhaps closest to providing answers as to why this is the case. In simple terms, the gut microbiome is the collection of bacteria, viruses, microflora and other microbes in our intestinal tract and scientists at our top research centres have been studying its links to all manner of ailments for over a decade. Although much of this is emerging rather than settled science, researchers have already discovered a systemic link between the diversity and health of our gut microbiome and our susceptibility to many diseases including IBD, food allergy, cancers, Alzheimer’s, depression and several auto-immune diseases. The precise causal connection has not yet been fully established, and mainstream medicinal doctrine is yet to embrace it, but there is growing evidence that the microbial ecosystem in our gut is a major indicator of our propensity to many chronic illnesses. Researchers suggest that one of the mechanisms at work may be the interface between our gut lining and the body’s blood and lymphatic systems. A properly functioning gut lining will allow only the required nutrients through into our blood stream, for use around the body, whilst preventing absorption of all the other contents of our intestines. According to the ‘leaky gut’ theory, when this system fails, and we suffer from ‘increased intestinal permeability’ (‘leaky gut’), the body’s immune system is forced to deal with many ‘foreign bodies’ that have been released into the blood stream. This in turn results in increased inflammation which is at the core of many chronic illnesses. The theory remains controversial among many mainstream medical practitioners, who cite a lack of clinical trials, but many others are embracing it as a major reason behind the significant rise of many auto-immune diseases and severe allergies over the last few decades.

And what is it that impacts the health of our gut microbiome perhaps most of all? Naturally, what we consume. It seems entirely obvious that what we put into our bodies directly and significantly influences our health. We are exposing our internal workings to whatever it is we swallow or breath. If we eat, drink or breathe poison we become sick and maybe die. If we smoke, we eventually die, actuarially at least. If we eat a Mediterranean diet, we live longer. If we live like the Japanese we live longer. People from the country-side live longer than those who live in cities. Athletes follow a strict nutritional plan to elevate physical performance. Human space exploration requires strict nutritional planning. We know all of this because the data are incredibly clear. What we consume is a major determinant of our health. It is true that microbiome scientists today cannot say exactly why or how the diversity of our microbiome contributes to the incidence of disease, but they understand enough to know that there is a systemic link and most likely causality. Incidentally, the diversity of the microbiome is also significantly impacted at birth with vaginal births and breast-feeding transferring microbes from mother to baby.

And yet, despite these advances and all that our instinct tells us, our entire healthcare system is set up as if we didn’t know the connection between lifestyle and illness, as if each patient that arrives with the symptoms of a chronic lifestyle disease is just another patient with another disease.

Why is this? Much has been written about the role of nutrition in the beginnings of Western medicinal doctrine. The phrase “Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food” has been attributed to Hippocrates. Whether or not that is true, at a certain point Western medicinal doctrine became all about treating the sick rather than about prevention. Not surprisingly perhaps given the explosion in disease during the industrialisation of the planet but that is basically where medical science has been ever since. Big pharma is big business and spends billions convincing us through one method or another that all we really need is more pharmaceuticals. Just spend an hour watching TV in the US and marvel at the advertisements for complex pharmaceuticals aimed directly at individuals, some with side effects that “might include death”. It’s also quite obvious that prescribing clinicians can be brought on side. Read up on the opioid crisis in the US or to a lesser extent the UK.

Imagine, by contrast, if the ‘cure’ for many cancers, heart disease, stroke, Type II diabetes and Alzheimer’s was actually a proactive lifestyle change rather than a reactive pharmaceutical, radiation treatment or surgery. Hint: it is, and the public health data are irrefutable. According to the Lancet, it is possible to prevent or delay the onset of dementia in as many as 35% of people through modifications to risk factors including increased child education and reducing hypertension, hearing disability, obesity, smoking, depression, physical inactivity, diabetes and social isolation. Research and clinical studies show that adopting at least three positive life-style adaptations from not smoking, reduced alcohol, healthy diet and regular exercise makes a significant difference in our propensity to develop dementia versus adopting just one or two of these lifestyle changes. Many other studies show that regular physical exercise is a major contributor to longevity more generally.

Another part of the narrative here relates to the way we anoint medicinal solutions. In order to be approved for sale or prescription to the public, pharmaceuticals go through incredibly rigorous research studies and clinical trials that often cost more than US$100,000,000 and take over 15 years to complete. A new cancer drug could cost as much as US$2 billion to bring to market. What chance is there for a prescription of more vegetables, sleep and physical exercise? Food and most other naturally occurring products are not required to go through clinical trials. But that doesn’t mean they can’t have the equivalent impact on our health. A doctor in the UK or US is more likely to prescribe aspirin than omega-3 fish oil to reduce the risk of heart attack despite large scale trials that show fish oil to be more effective. Clearly, with many illnesses, at a certain point in the lifecycle of the illness, only a pharmaceutical or clinical intervention will yield the desired results. Rightly, significant medical research is devoted to finding cures for diseases or treating those affected. Yet it is abundantly clear that we are not doing enough to prevent the diseases developing in the first instance. The cost in lives and dollars of not doing more by way of prevention is monstrous.

What can be done? I see five avenues of attack. First, healthcare policy makers must devote many more resources to public education, just as we did eventually with smoking, or as we did when the AIDs epidemic first broke. Second, we must change the way that we educate our health professionals so that their studies include more of the science of prevention. That means embracing nutrition as a core medical science rather than a branch of ‘alternative medicine’. Third, we can go further in taxing unhealthy behaviour, extending what we do with smoking and alcohol to sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) for example. Certain cities, regions and countries around the world have implemented taxes on SSBs resulting in reduced consumption. Fourth, more funding should be allocated to research into the microbiome and mitochondrial health and how it is affected by, among other factors, antibiotics, additives and chemicals in the food supply chain. The Quadram Institute is a new research centre in the UK set up to do exactly that. And fifth, health insurers – including single payer systems such as the NHS – must incentive healthy living. Some insurers have already begun this by reducing premia for cyclists much in the same way that we can reduce our car insurance premia by using technology to show that we are safe drivers. The point is, it’s not difficult but the impact on public health would be massive.

This article has not touched on the contribution of genetics in the propensity for developing certain illnesses and it is clear from the enormous amount of research over the last decade or two that genetics can be a significant factor in our propensity to certain diseases. Yet, we must understand the implications of these statistics. It is not fate that you develop an illness that your genetics pre-dispose you to. All of us can tilt the odds in our favour by adopting a healthy diet, regular exercise, good sleep and reduced stress. Nor should an individual point to the outliers that smoke, drink, eat badly, don’t exercise and live to 90 plus. The statistics are the statistics. There will always be outliers but that provides no comfort to the vast majority of us that fall within the predictive range of outcomes. It is a high stakes gamble with our health pure and simple.

Would we bet the house on the turn of a roulette wheel? No and partly because the result of the gamble is instant. You can lose your house immediately. Should the fact that we don’t find out if the gamble worked for 30 years lead us to different conclusions? And therein lies the issue. As humans we are happy to defer judgment day for just one more roll of the lifestyle dice. Instead we should be investing in our futures by adopting extremely easy lifestyle choices, giving up smoking, selecting the right diet, taking regular physical and mental exercise, getting good sleep and reducing stress. If we do that we will definitively be extending the length and quality of our lives.

Nor is it an excuse to say that there seems to be constantly conflicting advice on what a good diet is and whether it includes meat or carbohydrates or fat etc. The reality is that avoiding certain elements of modern food is not in debate, especially refined sugar, salt, processed carbohydrates, and ‘bad’ fat. Debate around the benefits of say, polyphenols in wine and coffee, or the avoidance of animal protein and fats will continue to rage, not least given the extensive funding efforts the food and beverage lobby, like the smoking lobby in the past, is able to undertake. We know enough with certainty to be able to recommend diets that will materially increase our longevity. In years to come we will look back on the diets we adopted in the past 50 years, and the way we process food, in the same way we now look back on smoking. We are creating the public health graphs of the 21st Century right now and we need to decide if we see that now or learn later.

Tom Speechley, SX2 Ventures, November 2019

At SX2 Ventures we invest in the business of human care. One of the areas we are most interested in is longevity and innovations that can be made to the primary care model to refocus resources on preventive steps especially lifestyle factors and non-invasive interventions prior to the onset of chronic illness.